Terrible things happened at many of Canada’s Residential Schools. But describing these institutions as instruments of mass murder is inaccurate.

By Ian Gentles

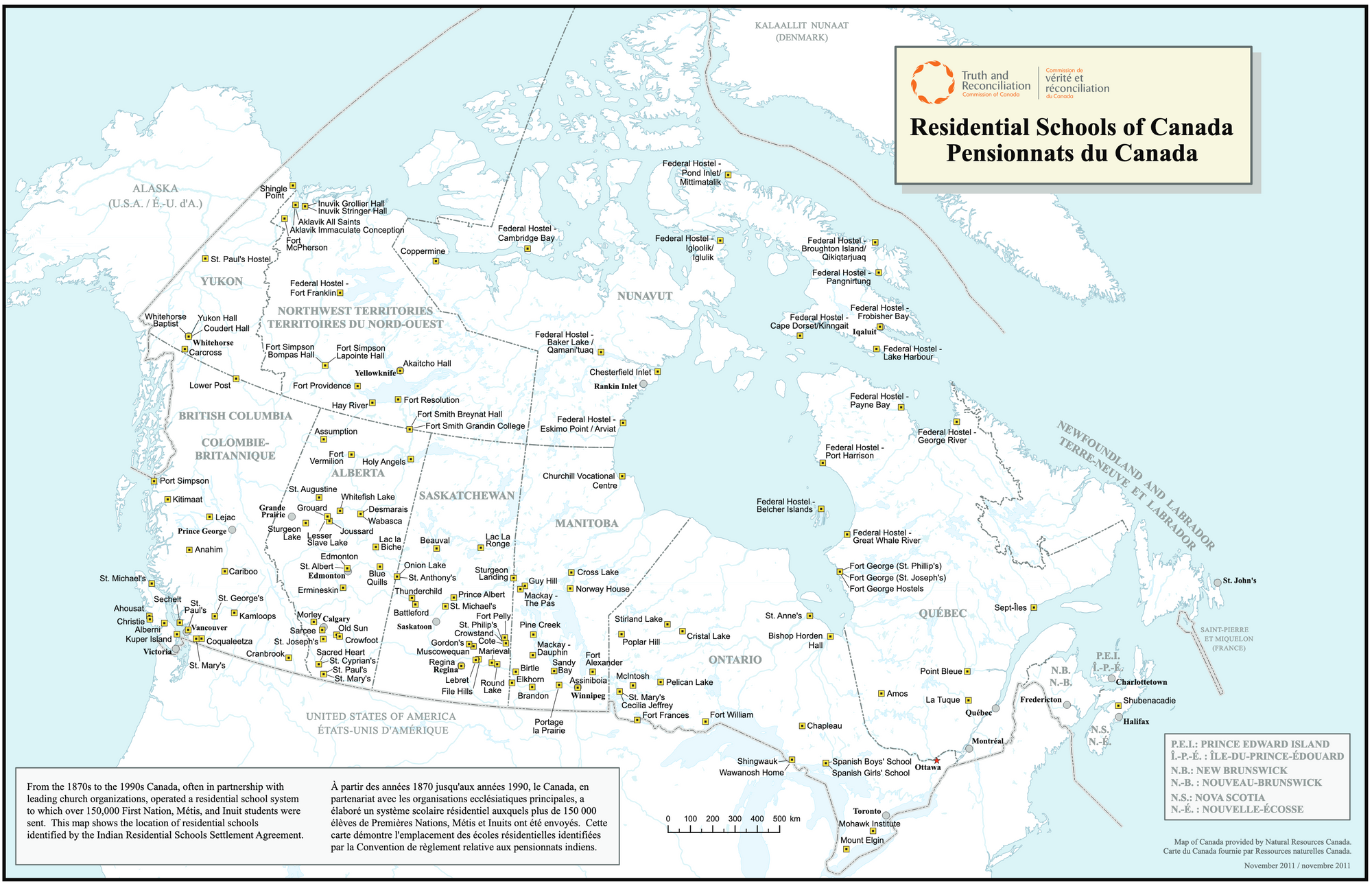

The movement to describe Canada’s system of Indian Residential Schools as a “genocide” has been gaining momentum since the late twentieth century. That momentum became stronger in 2021, when it was claimed that the unmarked graves of hundreds of Indigenous children who’d attended these schools had been found using ground-penetrating radar. While none of those claimed graves have yet been found, the social panic that followed the initial announcements has not fully abated.

In 2022, Canadian MPs unanimously voted for a parliamentary motion that described the schools as genocidal. Even the Pope has now used the word “genocide” to describe the schools and the larger project of assimilation they stood for—a notable development given that the Catholic Church ran almost 50% of these government-funded institutions during their period of operation, from the 1870s until 1997.

Indeed, the word genocide is now thrown around so casually in regard to the approximately 150,000 Indigenous students who attended Residential Schools, that it’s easy to forget how recently this allegation became popularized. In 1996, Canada’s Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoplesindicted Residential Schools for the “horrors” committed under their watch, leading the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs (as it was then named) to issue a statement to the effect that residential schools were guilty of creating a “tragic legacy.” The word “genocide” was not used.

Even in 2015, when Beverley McLachlan, then Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada, weighed in on Residential Schools, she described their mission to assimilate Indigenous children as “cultural” genocide; rather than genocide, full stop. This language was echoed that same year in a summary volume published in 2015 by Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which reported that for over a century, the government’s central aim had been to “cause Aboriginal peoples to cease to exist … which can best be described as ‘cultural genocide.’”

Over the last eight years, the qualifier “cultural” has fallen away. And it is now seen as heretical to challenge the claim that Canada’s Residential School system qualifies as a true genocide in the sense of the Holocaust, Holodomor, or Rwandan Genocide—despite the fact that such a classification remains questionable under international law. Indeed, some Canadian activists claim that even debating the applicability of the word “genocide” to the Residential School system is, itself, a “tool of genocide.”

Nevertheless, that is what I intend to do in the essay that follows.

Canada’s system of Residential Schools was founded by the government of Sir John A. Macdonald, the country’s first prime minister. The fortunes of Indians (as most Indigenous people were then described) were in decline, partly because the fur trade—which for many years had been profitable to white traders and Indigenous trappers alike—was no longer economically viable. A second factor was the decline of the buffalo hunt. By the middle of the nineteenth, the herds were thinning out. And in the spring of 1879, for reasons that have never been fully explained, the buffalo did not return to the western plains at all. Many found themselves in desperate straits, and there seemed a real possibility that the affected Indigenous communities would fade out completely.

Part of the Canadian government’s response to this crisis was the establishment of day schools and boarding schools that would offer Indigenous children an education that would prepare them to become “productive” workers (as the government would have defined the term) in the modern industrial society that Canada was then becoming. However, school attendance would not become universally mandatory until 1920.

The objective was unabashedly assimilationist, which is why it is now described by modern observers as racist, or even genocidal. But at the time, it was viewed as progressive. The hunting, trapping, and fishing that sustained many Indigenous communities seemed to be completely doomed. And it was believed that a new way of life based on agriculture, mining, and industry would offer a more promising future for a majority of the peoples we now call First Nations, Métis, and Inuit.

Macdonald’s government, which would remain in power for much of the latter nineteenth century, following Canada’s creation in 1867, was not unsympathetic to the needs of Indigenous people. In 1870, it responded to Louis Riel’s demand for a province for the Métis and other Indigenous peoples of the west by creating the Province of Manitoba and providing for its entry into Confederation. Macdonald ensured that the new province was provided with federal subsidies and strong representation in the federal parliament.

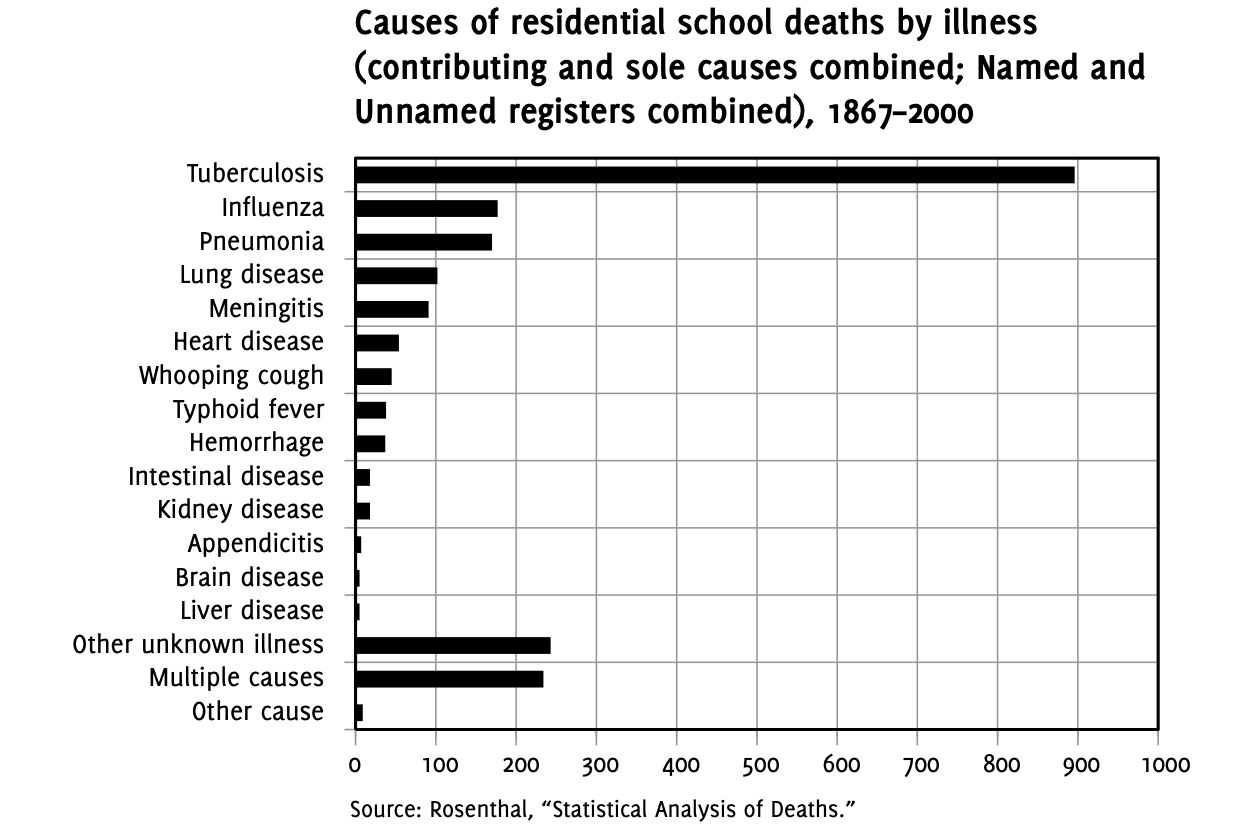

Like many other government projects—then and now—the Residential Schools were underfunded. And one reason why the actual operation of the schools was outsourced to Christian priests, nuns, and ministers was that this sort of devolution helped save money. Moreover, the early buildings were generally constructed on the cheap, badly heated, and poorly ventilated. In many schools, the students shivered during cold winter nights, and transmitted infections to one another in overcrowded classrooms. These included influenza, pneumonia, smallpox, whooping cough, diphtheria, and especially (as discussed below) tuberculosis.

But while all of this is true, the context was that, until well into the twentieth century, all Canadian children suffered what we would now consider to be shockingly high mortality rates. As discussed in more detail below, the death rates for Indigenous children tended to be much higher than for non-Indigenous children. But from the early 1900s onward, as Canadians’ understanding of public health became more advanced, Residential School administrators began embracing measures to reduce childhood mortality—in some cases, even pioneering new policies that had not yet been widely adopted elsewhere.

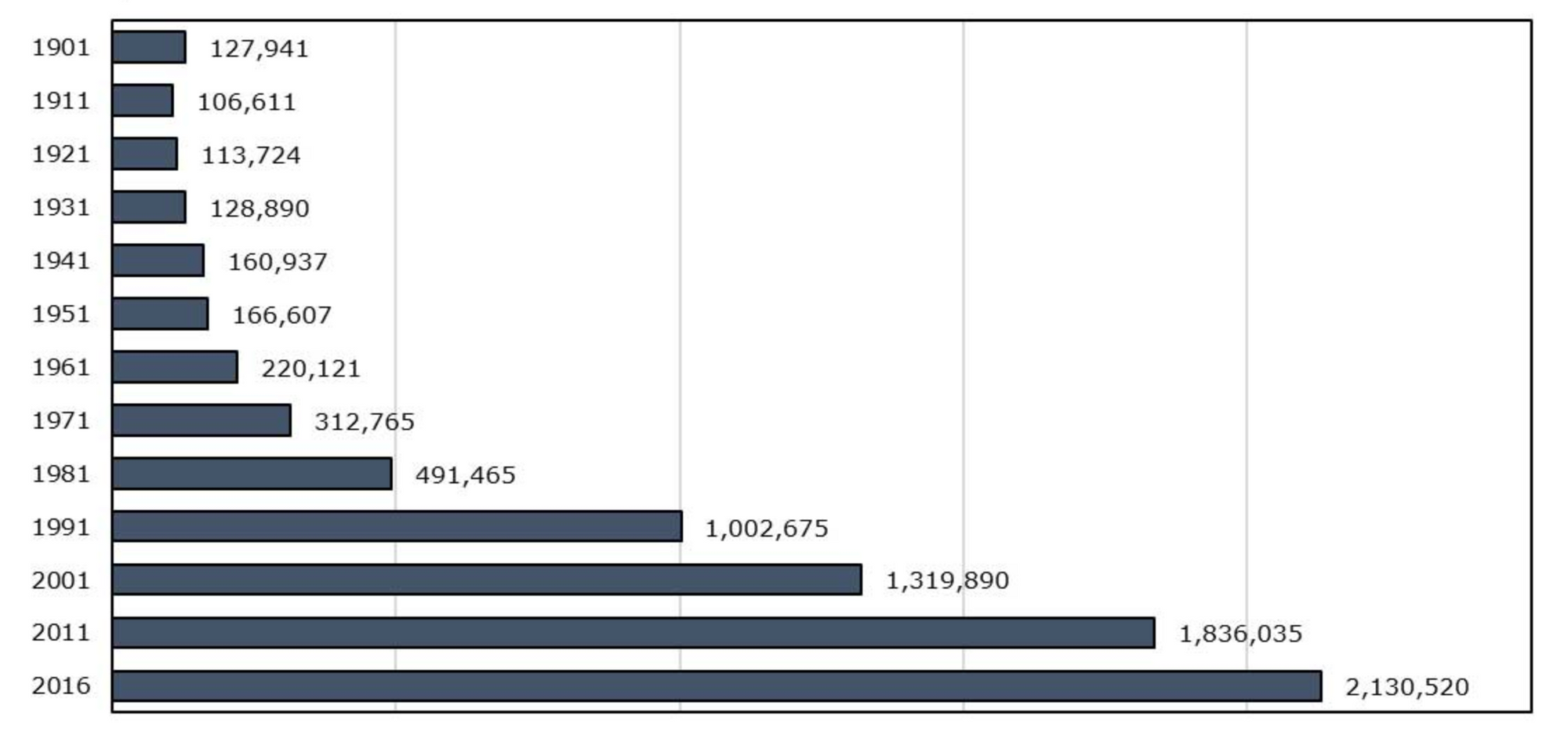

When Europeans first began arriving in North America, the Indigenous population of what is now Canada was at least 200,000, according to the best available academic estimates. (Some argue that it was much higher.) By the early 1900s, it had dropped to about 100,000. Despite many Indigenous communities having, on average, a higher birth rate than their non-Indigenous counterparts, the Indigenous population didn’t begin to rebound until after the First World War. (Since that time, it has risensteadily, and now stands at about 2-million.)

Canadians reporting Indigenous ancestry, by census year.

The greatest infectious killer of all in Canada during this period was tuberculosis (TB)—especially in Indigenous communities. Even as late as 1957, when the overall Canadian death rate for tuberculosis had fallen to just seven per 100,000, the death rate for the category then described as “Registered Indians” was still 42 per 100,000—six times higher. For the Inuit, in Canada’s far north, it was even higher: 179 per 100,000, or about twenty-five times the national rate. These facts surely constitute a stain on Canada’s national conscience.

Residential Schools were swarming with TB, as they generally did not refuse admission to children suffering from any contagious disease (though administrators did subject students to health checks, so they might at least monitor their ailments). Had schools enforced such a requirement, they would have had few students, since large numbers of First Nations children had been exposed to mycobacterium tuberculosisat some stage in their development.

A graph tracking Residential-School death rates published in the Truth and Reconciliation report.

While critics of Canada’s policies during this period will rightly note that such facts serve to indict the socioeconomic conditions of the Indigenous communities from which Residential Schools students originated, it was generally the case that children from the reserves brought tuberculosis into the schools, and not the other way around. “In no instance was a child awaiting admission to school found free from tuberculosis; hence it was plain that infection was got in the home primarily,” wrote Dr. Peter Bryce in his 1907 Report on the Indian Schools of Manitoba and the Northwest Territories. He blamed this fact on the crowded and unsanitary conditions on Indigenous reserves, where TB was far deadlier than in schools, in large part thanks to the federal government’s neglect.

A graph tracking Residential-School deaths attributable to illness, published in the Truth and Reconciliation report.

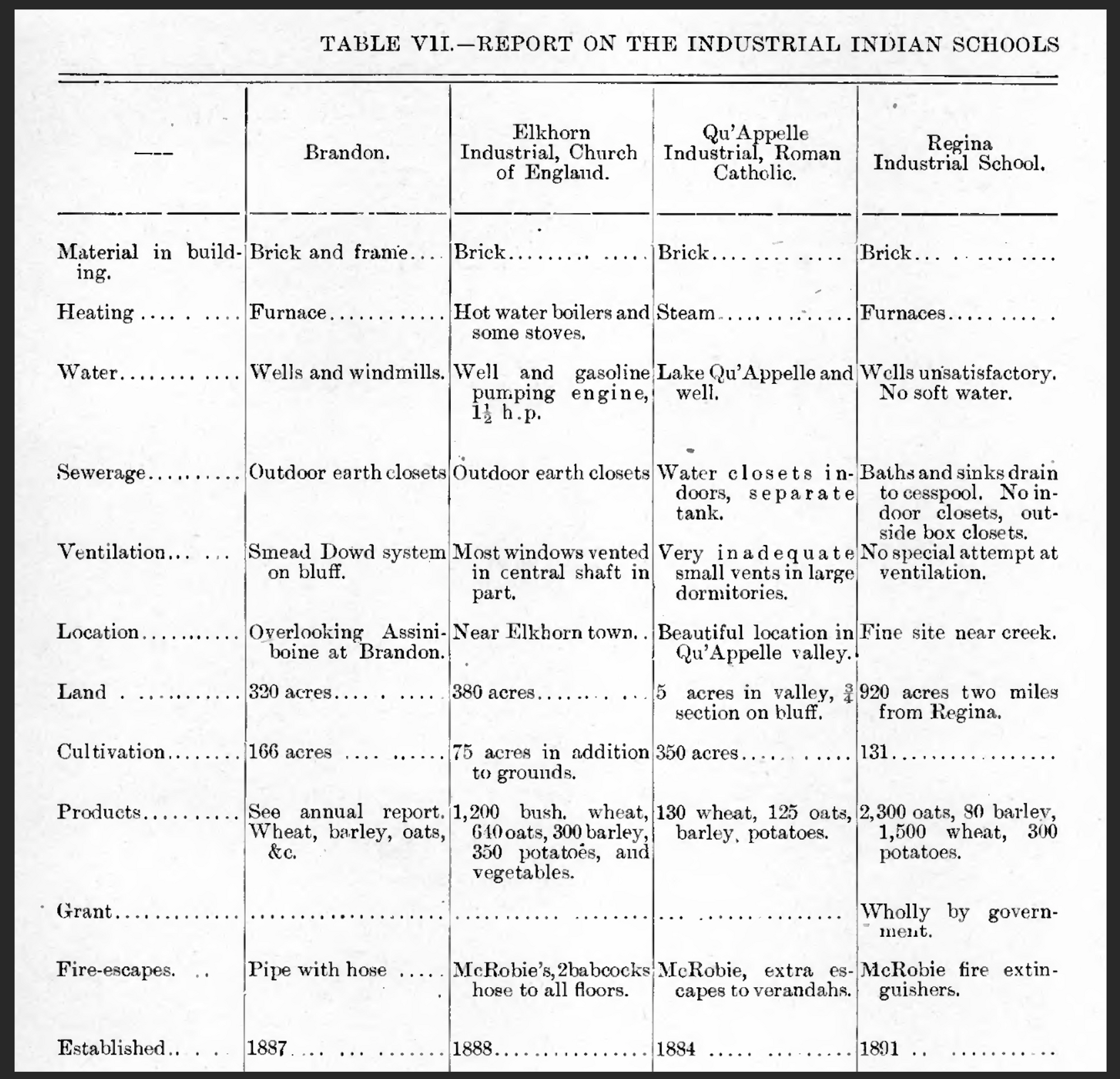

Dr. Bryce, then Chief Medical Officer in the Department of Indian Affairs, had issued a scathing indictment of the Residential Schools’ deplorable sanitary conditions, which, he concluded, were contributing to the unchecked spread of TB. Applying their (often scandalously limited) resources, many school administrators and government officials took his words to heart, and upgraded their schools so as to improve ventilation and hygiene more generally. For example, the largest school in the entire national system, on the Kamloops reserve in British Columbia, installed a large septic tank for sewage-treatment purposes—an important undertaking by the standards of the day.

One of many tables contained in a 1907 report written by Dr. Peter Bryce, detailing information pertaining to Residential Schools he had inspected.

Over the following fifteen years, about 30 Residential Schools were built or remodelled to the new, healthier standards. This is reflected in the data. Mortality from TB in Residential Schools fell from about 900 per 100,000 in 1907 to fewer than 100 per 100,000 in 1921, a more than nine-fold decline.

At the beginning of the school year in 1938, the Blue Quills Residential School in Alberta took the precaution of arranging lung X-rays for all its students. A school report from the period records that one Dr. Davison “came to the School to give the skin test to the newcomers. He said that the four girls at the hospital, being treated for T. B., will soon be able to come back to school.”

Such reports come from surviving fragments of Residential School documents—such as old issues of the school newspaper at Blue Quills, the Moccasin Telegram—and so it is impossible to make any kind of definitive generalization about such practices. But certainly, even anecdotal reports such as these are difficult to square with the idea of genocide.

Cover page for a 1948 edition of the Moccasin Telegram

Steps also were taken to eliminate bovine tuberculosis from the herds that supplied milk to the schools. (This was at a time when milk pasteurization, which was not uniformly adopted in Canada until well into the Cold War period, was still seen as an innovation.) Medical inspectors were appointed in each province to visit the Residential Schools, many of whose facilities had been expanded to include hospitals that served local Indigenous reserves.

During this period, some of the medical officials charged with these duties implored the government to provide more personnel and resources to help Residential School students. Dr. George Adami, a Professor of Pathology at McGill University in Montreal who worked with Dr. Bryce in combating childhood TB, wrote, “I can assure you my only motive is a great sympathy for these children, who are the wards of the government and cannot protect themselves from the ravages of this disease.”

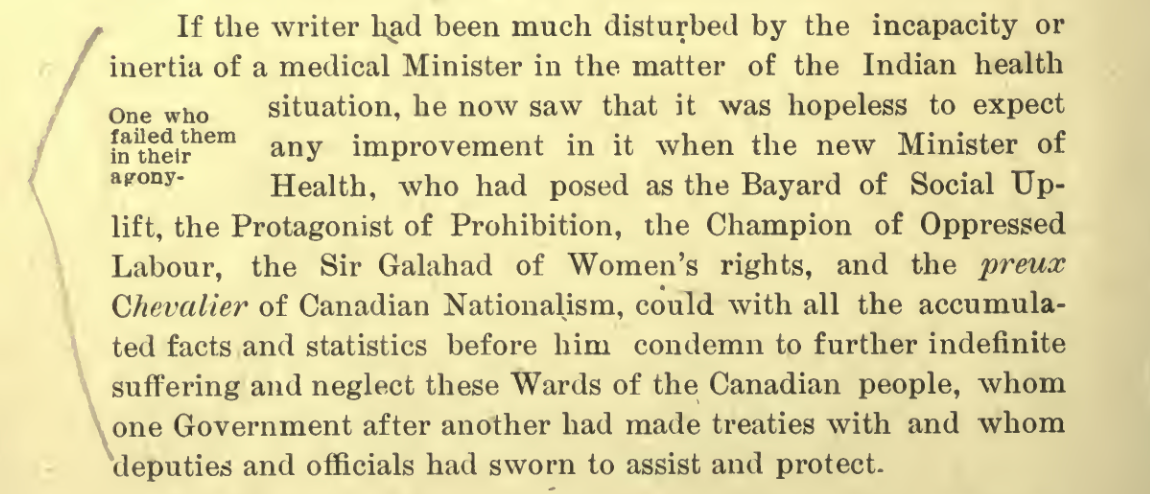

Alas, their entreaties often fell on deaf ears in Ottawa, where many bureaucrats and politicians seemed fixated on cutting costs—a state of affairs that Dr. Bryce dramatically denounced in his writings.

An excerpt from The Story of a National Crime, a 1922 book written by Dr. Bryce, (archly) describing the deadly negelct of government actors in respect to conditions at Residential Schools.

Certainly, many fewer Residential School students would have perished from disease if governments had provided more resources to administrators and local medical personnel. Nevertheless, new medical technologies did have dramatic positive effects. In 1933, Dr. George Ferguson launched an experimental trial with the then-new Bacillus-Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine. To demonstrate his conviction that this would help prevent the spread of TB among Indigenous people, Dr. Ferguson first vaccinated his own six children. His program at Fort Qu’Appelle, Saskatchewan was a remarkable success, featuring an 80% reduction in active cases of TB among those vaccinated, and no deaths.

All of these achievements were ultimately overshadowed in the 1940s by the introduction of streptomycin, an antibiotic that could effectively treat tuberculosis—the first of many such drugs that eventually would help virtually eliminate tuberculosis in Canada. From the World War II period onward, the incidence of TB plummeted in Canada.

Vaccine pioneer George Ferguson being honoured in 1935 by the Qu’Appelle Valley Natives as Muskeke-O-Kemocan (Great White Physician).

Among Canadian First Nations populations, the incidence of tuberculosis fell by 92% in the quarter century between 1930 and 1955. Research summarized in the Historypublished by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission informs us that from 1943 to 1953, the annual TB death rate for the First Nations population as a whole dropped from 627 per 100,000 to 100 per 100,000. During the same period,the annual TB-associated death rate in Residential Schools went from about 230 deaths per 100,000 to 20 deaths per 100,000.

These statistics indicate that the rate of TB mortality for Residential School students not only fell sharply in absolute terms following the introduction of these new medications: It also fell in relation to Indigenous TB mortality as a whole. In 1943, the TB mortality rate for First Nations Residential School students was about one third the rate for First Nations overall. By 1953, the corresponding number was about one fifth. And it is worth noting that while the last Residential School closed its doors more than a quarter century ago, the rate of tuberculosis among First Nations people in Canada now remains a shocking forty times higher than among the rest of the country’s population (although, thankfully, deaths from TB are now extremely rare).

A somewhat analogous pattern may be observed in regard to the waves of Spanish Influenza that struck the world in 1918-19. First Nations families were ravaged by the epidemic, which carried off the young(under age 20) more than any other age group. And the mortality rate for these communities was many times higher than in the general Canadian population. (In B.C., for instance, it is known to have been nine times higher.) But in the Residential Schools for which we have precise information, the death rate associated with the Spanish Flu was only about 27% of the rate for First Nations people as a whole.

Once the Canadian medical community was properly roused to the project of improving public health in Residential Schools during the interwar period, significant advances also were made against other diseases—such as trachoma, a once common ailment that could cause blindness before the development of an effective sulfanilamide-based treatment in the late 1930s. At the aforementioned Blue Quills school, officials monitored students for symptoms. By one student’s report, one Dr. Walls “came to see how our eyes were. During class, we all went up and it was not long before all our eyes were examined. Dr. Walls was very pleased with the appearance of our eyes.” A 1935 government reportindicates that “the number of acute cases of trachoma in the schools has greatly diminished,” while also encouraging officials to remain vigilant:

This does not mean that the disease is nearly conquered. There is a great deal of practically unreachable trachoma among the older people on the reserves. Many of the young children coming into the schools are affected, and undoubtedly some of those whose eyes have been cleared up in school will forget their training and become reinfected after discharge. Their treatment and training in school, however, is bound to be of great value. They will protect themselves better, will recognize the disease in early form in their children and neighbours, submit more readily to treatment, and know how to carry out directions intelligently. The department anticipates a long struggle, but is very hopeful of the final outcome.

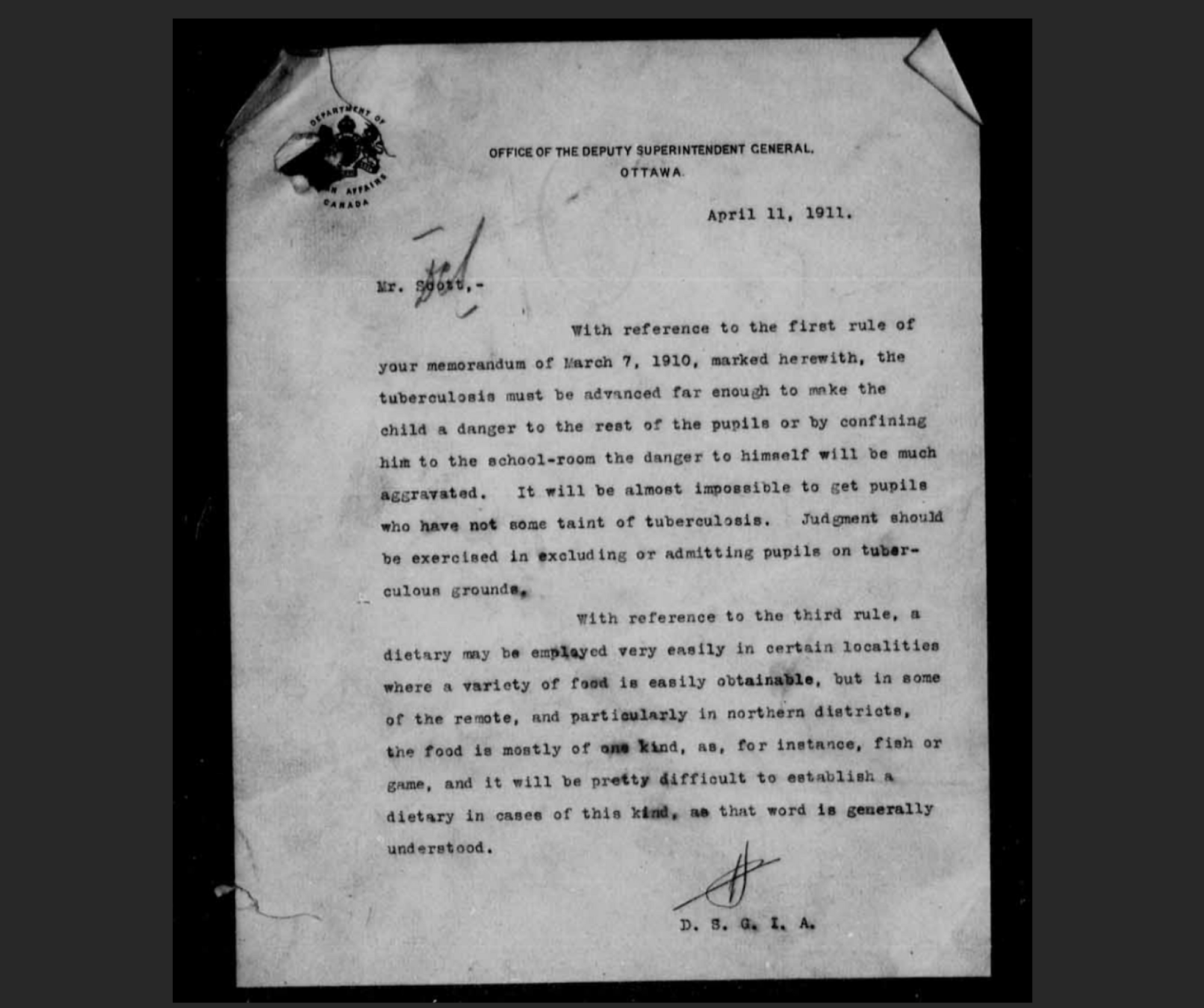

The debate about the legacy of Canada’s Residential Schools is sometimes conducted on the assumption that public officials of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were completely insensible to the deadly hardships imposed on Indigenous communities by European settlers. But the historical record indicates that, even before World War I, government ministers and medical experts were wrestling with the best way to—as Hayter Reed, Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs, put it—promote a “gain in general health, in physical growth, in freedom from sickness and deaths and in school attainments” for those attending Residential Schools.

Archived government correspondence from 1911, indicating a discussion on the best means to address health and nutrition concerns regarding Residential School students.

A few decades later, Canadian Medical Association Journalreaders were informed that the fight against tuberculosis in First Nations communities was not only a practical imperative, but also a moral one, as settlers were the ones who “took and occupied his [i.e., the Indigenous] country, [and] especially because we brought him the disease.”

As noted above, such admonitions often were ignored by Ottawa politicians. “Despite the growing provincial pressure for action on tuberculosis prevention, in 1937, the federal government imposed another round of cuts on Indian Affairs,” the Truth and Reconciliation Commission reported. In January of that year, “the director of Indian Affairs … instructed all staff that ‘their duty in the immediate future is to keep the cost of medical services at the lowest point consistent with reasonable attention to acute causes of illness and accident. Their services must be restricted to those required for the safety of limb, life, or essential function.’”

This language will appear scandalous to modern readers. And, to repeat the point, it is absolutely true that many Indigenous lives likely would have been saved if the Canadian government had spent more freely on health services for patients, both Residential School students and otherwise. But it is important to remember that millions of other sick Canadians suffered from the same frugal attitudes. Socialized medicine didn’t become a universal feature of Canadian public policy until well into the 1960s—more than three decades after these words were written.

As to the allegations of substandard food and inadequate servings at Residential Schools, many are no doubt true. But again, historical perspective is important. The National Truth and Reconciliation report, for instance, contains a reference to a 1931-era menu at the Gordons Residential School in Saskatchewan as an example of the poor and inadequate diet offered the students. Yet the authors do not mention that Canada was then in the depths of the Great Depression, when families all over the country worried where their next meal would come from. The sample menu referenced by the authors is as follows: “Breakfast—boiled eggs, rolled oats, sugar, and milk, bread, butter, tea, cocoa; dinner [the mid-day meal]—soup, cold roast beef, vegetables, potatoes, bread, rice pudding; supper—beef stew (including vegetables?), bread, butter, jam, tea.” Even if one assumes small portions and an unappetizing presentation, this hardly seems an insufficient diet by Depression-era standards.

A study recently published in the Canadian Journal of Economics found that prior to 1950, children placed in Residential Schools were, indeed, often undernourished—thanks to government underfunding. However, reforms instituted following World War II resulted in often dramatic improvements in students’ health:

We find evidence that, on average, residential schooling increases adult height and the likelihood of a healthy adult body weight for those who attended. These effects are concentrated after the 1950s, when the schools were subject to tighter health regulations and students were selected to attend residential school based partly on their need for medical care that was otherwise unavailable.

Depending on the region of the country, Residential School students born after 1930 experienced an average height increase of up to an inch—an indicator of improved health and living standards.

Of course, the well-being of a student cannot be captured with merely physical indicators. As many former Residential-School students have attested, there can be crippling psychological stresses associated with being separated from one’s home community. At some schools, severe forms of corporal punishment were common, not to mention (less common, but far more scarring) instances of sexual abuse. Since the purpose of these schools was to assimilate Indigenous children into white society, moreover, children often were forbidden from speaking their native languages and practicing traditional forms of spirituality. Even though these students were free to return to their home communities during the summer months, their exposure to their ancestral culture was diminished. These facts are at the root of the charge of “cultural genocide” that became common in the 2010s.

At this point, however, it should be noted that only a minority of First-Nations children ever attended a Residential School, as their purpose was largely to supply a school for communities that didn’t already have an accessible day school located on (or very close to) their reserves. And in many cases where they did attend, those schools had been set up with the support of local Indigenous communities. As noted above, it was only in 1920 that Canada’s federal government made such schooling compulsory for Indigenous youth.

Even at peak attendance, in the 1930s, Residential Schools accounted for only about one-third of First-Nations children who were attending any school. By 1968, it was down to 13%. And by the early 1980s, there were only about 20 facilities in operation across the entire country. It’s hardly unreasonable to scrutinize Residential Schools as being a factor in the decline of Indigenous culture. But the available data suggest that their effect in this regard has been overstated.

Another complication in the narrative is that, as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report states, Indigenous parents and leaders often preferred Residential Schools over racially integrated provincial public schools—in part because of (not unreasonable) fears that Indigenous children would be bullied in a racially mixed environment. In 1961, for instance, the principal of the a Residential School in Sioux Lookout, Ontario, warned government officials that

many of our children who will be attending the integrated classes next term, or should be, have indicated to me that they are not going to return to school as they do not like the idea of going to school with the other children. With many of these youngsters, I do not feel there will be any great problem, however there are families who are quite put out by the thought of their children attending the school in Sioux [Lookout].

In other cases, Indigenous parents objected to their children being transferred out of the boarding arrangements at Residential Schools, on the basis that they didn’t have the means to care properly for their children at home—a phenomenon that became apparent after 1950, when the federal Indian Affairs Department began systematically transitioning away from Residential Schools, so as to enrol more children in day schools and provincial public schools. As late as the 1960s, a Saskatchewan official reported that they were “inundated with applications [for enrolment of children in Residential Schools.] That was one of the times of the year I dreaded the most … when we had to go through these applications and turn down any number of people.”

One thing that should be emphasized here is that Indigenous parents consistently exercised agency over the education of their children—a fact somewhat obscured by efforts to (falsely) portray the Residential School system as a network of prisons full of children who were (literally) ripped from their helpless parents’ arms. There is no doubt that many Indigenous parents sent their children to Residential School because (after 1920, at least) they had no other legal option. But to suggest that most Indigenous parents passively submitted to government pressure is insulting to them. Indeed, there are numerous examples of Indigenous communities negotiating extensively with government officials over the schooling question—which featured, in some cases, Indigenous leaders campaigning actively in favour of residential schooling options.

One study of Residential Schools in British Columbia, for instance, notes that heads of families would sign contracts with the schools, stipulating the nature of the education their children would receive. While cases of forced enrolment undoubtedly occurred, one scholar found, “they were scattered and usually unauthorized.”

Parents often had firm expectations. One late nineteenth-century government document, for instance, reports of one First Nations that “although there are only a few children in this band, the older members take an active interest in education, as they wish to see all their people put on a level with their white neighbours.” Others expected that their children would experience improved health at school; or sent their children to Residential School because the other parent had died, or their marriage had broken down. In two B.C. schools for which records have survived, almost 50 per cent of the students were orphans. Other parents simply concluded that their children would fare better in a Residential School than amidst the challenges of life at home.

According to one former student at the Shubenacadie Residential School in Nova Scotia, “I could tell you that our lives outside the Residential School was bad enough that she [my mother] felt … that it was better for us to be there than with other family members … We were safer in her eyes to be there than at home.” Tragically, many Residential Schools betrayed these expectations. But many did not. And on balance, the research indicates, “Residential School does not seem to harm parental socio-economic status.”

Needless to say, the fact that many Indigenous families often felt they had no better choice than to let strangers care for their children during the school year does not speak well for their status in Canadian society. Certainly, I don’t want my argument here to be misinterpreted as asserting that these parents were fortunate. The desire of parents to be with their children is universal. And the fact that many still chose to send their children to Residential Schools speaks to the dire straits in which they found themselves. This state of affairs does not speak well for Canadian society. But it also does not suggest a genocide in progress.

As already noted, there are numerous accounts of Residential School students enduring strict forms of discipline—including forms of corporal punishment that would be seen as inhumane and criminal in our own era. Getting a strap on the palm or posterior, or a wooden ruler on the knuckles, was hardly uncommon. What is often forgotten is that corporal punishment was standard practice in Canadian schools until the 1960s and beyond. Some private schools, such as Selwyn House in Montreal, didn’t retire “the cane” until the 1980s.

It is absolutely true that corporal punishment meted out against children is alien to most Indigenous cultures (a fact that was noted as early as the sixteenth century by the first French explorers to Canada). But in general, the men and women staffing Residential Schools did not see themselves as imposing disciplinary measures that their own (white) children would not be subject to at their own schools.

In some cases, there were instances of real sexual predation and sadism—as has been the case at other Canadian schools, sadly. But according to the Indian Residential Schools Adjudication Secretariat—a quasi-judicial tribunal established to assess legal claims made under the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement of 2007—“the vast majority of schools in most decades have five or fewer cases of [physical or sexual] abuse.” It need scarcely be noted that even a single case is one case too many. But no society, Indigenous or otherwise, is immune to the problem of sexual abuse. I will not dwell here on the high reported rates of sexual abuse in some Indigenous communities, because the roots of this problem are complex (and often tied up with the effects of colonialism). But suffice it to say that while some Indigenous students left safe reserves to become abuse victims at Residential Schools, there were also students for whom the level of risk actually increased when they went home for their summer break.

If Residential Schools were indeed bent on genocide, of the cultural variety or otherwise, how are we to explain the array of both extra-curricular activities and skills training that most of them appear to have provided? A 1941 government report offers us this glimpse into some of these:

The progress made at Indian day and residential schools in the Province of British Columbia has been particularly gratifying. In addition to the regular academic courses, special vocational courses have been successfully organized. These courses, for girls, consist of the treatment and spinning of locally grown wool and the knitting of woollen garments, Cowichan sweaters, and socks, dressmaking, fruit preserving, crochet work, and home management; and for boys, boat-building, auto mechanics, Indian arts and crafts, and elementary agriculture. The Koksilah, Inkameep, and Ste. Catherine schools have been outstandingly successful in the organization of these courses, all of which are based on the needs of the Indians on the adjoining reserves. The teacher in charge of the Inkameep Indian day school has succeeded in the dramatization of a number of Indian legends. The presentation of these at the Banff Drama School created a great deal of interest amongst Indian educationists in Canada and the United States.

Another report, this one from 1961, provided this description:

”Indian students are encouraged to participate with non-Indians in such extra-curricular activities as track and field contests, as well as meetings of Guides, Scouts, Cadets, and 4-H clubs. Indian pupils enjoy participating in music and drama festivals as well as contributing many excellent items for display in exhibitions of school work and of Indian craft. School bands are not uncommon, and several excellent groups of dancers are active among Indian students. To enrich their experience, tours are sometimes arranged to local historic or scientific points of interest in connection with their school studies, or to nearby industries or places of employment, to introduce older students to the ‘world of work’ outside the reserve.”

La Tuque Indian Residential School Hockey Team, Les Indiens du Quebec, photographed in 1967.

This helps explain why there are a surprising number of testimonies from former Residential School students attesting to happy experiences. For instance, Tomson Highway, one of Canada’s most distinguished First Nations authors, has written in unmistakably positive terms about how the Guy Hill Residential School near The Pas, Manitoba helped launch him on a professional musical and literary career that would have been otherwise impossible. Run by the Oblate Fathers and Sisters of St. Joseph, the school was situated on the edge of an “emerald-watered lake.” Its facilities, he writes, constituted “a labyrinth … a kingdom of magic.” At night, “with the crisp clean sheets, warm wool blankets and central heating I am in heaven.” Elsewhere, he has declared,

Nine of the happiest years of my life I spent at that school … There are many very successful people today that went to those schools and have brilliant careers and are very functional people, very happy people like myself. I have a thriving international career, and it wouldn’t have happened without that school.

Members of The Sturgeon Landing, Saskatchewan, Residential School hockey team.

The late Senator Len Marchand also reported positively on his experience at a Residential School. Notably, he attended the Kamloops school, whose former grounds are routinely described in Canadian media as the site of unspeakable horrors.

Marchand enrolled in the 1949-50 school year, at the age of fifteen. The classes, he wrote, took place in “big, well-lit rooms, with desks as modern as any you could have found on the west side of Vancouver in 1949. And the teachers were just as good.” Marchand enjoyed playing sports at the school—baseball, basketball, and hockey. He took pleasure in the achievements of his fellow students, and wrote proudly about the school’s Holstein cattle winning blue ribbons at an agricultural air, and Sister Anne Mary’s “superb” choir, which “cleaned up at the annual local music festival.” He declared, “I was never abused, and I never heard of anyone else who was mistreated at the Kamloops school.” About the priests, nuns, and other religious officials, “they meant well by us, they genuinely cared about us, and they all did their duty by us as they saw fit.”

This is the very same Kamloops school where, we have been assured since 2021, the bodies of over 200 children supposedly lie in unmarked graves, the presumed victims of systematic criminal behaviour—even mass murder. The fact that no bodies have been found should not surprise those who know the school’s history.

When alumni from the Kamloops school organized a reunion for former students in 1977, no fewer than 280 individuals showed up—including well-known figures such as Marchand and former principal Bishop Fergus O’Grady. According to one account, “events included Indian dancing with Ernie Philip; slides of the ‘good old school days’ presented by Father Noonan, ‘where many of the students will recognize themselves’; more slides presented by former Indigenous teacher Benny Paul; ‘Bone Games’ and a salmon barbeque and dance.” I haven’t the slightest doubt that, as with all boarding schools, some alumni of the Kamloops Residential School have dark memories of their time there. But truly genocidal institutions do not host joyous two-day reunions featuring slideshows and visits from former administrators.

1991 reunion photo at Shingwauk Indian Residential School in Ontario.

Another well-known First Nations writer, Richard Wagamese, wrote about his mother’s experience at the Cecelia Jeffrey Residential School outside Kenora, Ontario. “My mother has never spoken to me of abuse or any catastrophic experience at the school,” he wrote in 2008. “She only speaks of learning valuable things that she went on to use in her everyday life, things that made her life more efficient, effective and empowered.”

As an aside, it’s worth noting the recent campaign, led by a number of public figures, urging the criminalization of something called Residential-School “denialism.” While this term has been vaguely defined by campaign proponents, it seems that the object of such a (presumably unconstitutional) law would be to censor anyone seeking to present Residential Schools as anything but instruments of abuse and cruelty. As the testimonials above indicate, a primary effect of such a law would be to criminalize Indigenous people offering honest recollections about their own experiences in regard to Residential Schools. Even the staff who worked at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, were they to republish certain writings produced by that body, might be held criminally liable under such a dubious law.

Other (apparent) Residential-School “denialists” would include a number of less well-known former students who testified to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Many of them are included in a document created by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission called The Survivors Speak.

Speaking of his two-and-a-half years at the Stirland Lake School in Ontario, Paul Johnup stated, “I learned things there … I got to know people … from other communities… I learned carpentry, mechanical, electrical.” Lillian Kennedy related, of her time at the Fort Alexander School in Manitoba, “I learned lots from the nuns … And I got along with everybody. I had lots of friends.” Martha Mingoose spoke of the times she shared with her beloved friends at the Cardston School in Alberta: “We always laughed, we always shared stories, we always talk[ed] Blackfoot.” Alphonse McNeely, who attended the Aklavik School in the Northwest Territorries, said there were frequent school picnics where they “played all kinds of games on the lake, and … just [had] fun.” Saturday was the highlight of the week for the boys at The Presbyterian School in Kenora, B.C., Donald Copenace recalled, because a big box of comic books would be brought out for them to dive into. Mary Rose Julian valued what she learned at the Shubenacadie School in Nova Scotia, where “I learned English. That was my objective for going there in the first place … I was there a year and a half; a nun never laid a hand on me.”

Percy Tuesday, who, like Donald Copenace, attended the Kenora School, reports having stood up for himself and winning justice from the principal. He and his friend were keen guitarists who loved to jam together. One day, a supervisor confiscated his guitar, apparently for no reason. “So I went, I went storming up to the principal’s office, and I told him, ‘this guy took my guitar, I want it back now.’ And I was, I was mad. I had it back within ten minutes.”

These are all the memories of individuals. And it is important to emphasize that the majority of witnesses appearing before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission offered recollections that were far more negative. Many of the stories in this latter category have been told and retold in great detail in the Canadian media. And they are an important part of the historical narrative—even if (as with the positive stories) many are impossible to prove or disprove.

(It is also the case that, as a matter of statistical representation, those students who report negative experiences have more of an incentive to make their stories public, since they are typically seeking justice or accountability—a more urgently felt moral project than simply reporting that everything was fine.)

What isprovable is that organized sports were typically a big feature of student life at Residential Schools. Gyms, skating rinks, and playing fields were common facilities. A few institutions, such as the Kamloops School had swimming pools—a rarity at most Canadian public schools during the early and mid twentieth century. Some students said that playing sports was the main thing—sometimes, the onlything—they liked about the schools. It wasn’t just fun—it instilled a sense of pride and accomplishment. At the Blue Quills school, Alice Quinney reported, “track and field day was a day when your … parents got invited to come and watch you perform in your track events.”

At the Residential School in Beauval, Saskatchewan, one principal exhibited a particular interest in hockey. “We started having new skates [and two sets of sweaters], Toronto Maple Leafs and the Montreal Canadiens,” according to one report. “And Maple Leafs, we used them at home, and then when we go out and play, we have to be Canadiens.” Orval Commanda recalled that a wide range of sports played a positive role in his life at the Spanish, Ontario, boys’ school, which boasted basketball, track events, pole vaulting, high jumping, shot putt, hockey, softball, baseball, and lacrosse.

Undated photo of the football team at the Spanish, Ontario Residential School.

Other students focused on the arts. A dance troupe at the Kamloops Residential School, run by one Sister Leonita, became well-known throughout British Columbia—though participants reported decidedly mixed memories of the required training regimen. Jean Margaret Brown recorded that “being in a dance troupe, I was made to feel special. But the work that we did to be in that dance group was really, really harsh.”

By the 1960s, famous Indigenous Aboriginal artists such as Henry Speck, an alumnus of Alert Bay Residential School in British Columbia, were being brought into some schools to give lessons in drawing and carving—experiences that artistically inclined students later recollected as being inspirational.

A sample from “The Trailblazing Art of Chief Henry Speck”

Almost all of the material I am citing here comes from official Truth and Reconciliation Commission documents published in 2015. And as I review those documents, it is amazing to think that in the space of just eight years, simply repeating this information has become taboo—a form of suspected “denialism.” The same is true of the more general acknowledgment in The Survivors Speak, that

many students have positive memories of their experiences of residential schools and acknowledge the skills they acquired, the beneficial impacts of the recreational and sporting activities in which they engaged, and the friendships they made. Some students went [on to] develop distinguished careers.

Visual corroboration may be found in the over 20,000 photographs contained in the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation archives. Unfortunately, many of these photos don’t feature dates, or even information about the school being depicted. Moreover, it should also be noted that (for the most part) the only people who had cameras were officials connected with the school in some way. And so it should be expected that the choice of subject matter would reflect the photographers’ desire to capture the school in a positive light. Needless to say, few were anxious to take photos of decrepit facilities or cruel behaviour.

With those caveats in mind, it remains notable how many pictures show rows of students, often smiling and well-dressed, betraying no indication of being sick or malnourished. In many cases, the students seem lost in their artistic or athletic pursuits, oblivious to the camera. There is little evidence of this being professionally curated or polished propaganda, as the photos often seem to have been taken by amateurs who are simply collecting shots for a yearbook or student newspaper.

Buried in the archives are back issues of school magazines, written, edited, and published by the students themselves. Again, skepticism is warranted: Then, as now, this kind of student journalism was done under the supervision of educators and school administrators, none of whom were interested in shocking investigative exposés. And so it is no surprise that their tone is consistently upbeat.

That said, they do catalog an extensive variety of extra-curricular activities that can’t have been invented by the writers. The Moccasin Telegram, published by students at the above-mentioned Blue Quills School in Alberta, included articles in both English and Cree. One Grade 5 student reported, “in the girls’ room, we have a new radio this year, which Father Balter bought for us. We enjoy it very much. We like best the dance music and the cow-boy songs.” Another student, also in Grade 5, wrote that “we played foot-ball against the Indian men. The score was 3 to 2 in favor of us. In the afternoon, we played baseball with them and we won the game, 7 to 4. Father bought us a base-ball out-fit. ”

Another entry, this one from a student named Victoria Janvier: “On Father Balter’s birthday, we had a big picnic… When we got there, all the girls went in wading in the water. Then the boys started to play games … After the games, we took our dinner under the trees … Then we had more games and then it was time for supper … When the boys and Sisters were back, we had fire-works … That was the nicest holiday we ever had.”

“This year, we go often sliding down hill and have lots of fun,” wrote a student named Caroline Cardinal in 1938. “We go everyday after dinner and at four o’clock till half past four … Father gave us thirty-six new sleds this year and we still have the sleds from last year, too.”

Two years later, a student named Caroline Piche wrote that “fifteen of the big girls went for a sleigh ride. One of the Sisters and two boys came with us. It was a little cold, but we did not care … We went as far as St. Brides, which is about eight miles from our School … While coming home, we tipped over, but I am glad to say that no-one was hurt. Some were all covered with snow and many of us lost our rubbers. After this … it was quite dark already … We were all cold, but we surely enjoyed our trip even though we tipped.”

The records also feature a variety of first-hand accounts left by nuns who taught at a variety of Residential Schools. They kept chronicles over a period of many years, documenting their work on a daily basis. And although media descriptions of Residential Schools now often casually dismiss all of these educators as cruel and predatory racists, this material—typically composed not as historical propaganda, but as private recollections—tells a different story.

From these chronicles, we learn of the great love that many nuns had for the students under their care. Since they lived in the schools full time, they saw themselves as far more than teachers. They nursed students with longstanding illnesses such as tuberculosis (exposing themselves to such diseases in the process). They also dealt with epidemics of measles, scarlet fever, whooping cough, and influenza. Rather than go home to their parents, sick children sometimes remained at school because there they would get better care, and help prevent the infection of reserve populations.

Undated photo of nuns from Marieval Residential School in Saksatchewan at a picnic.

They also provided treats for the children, like trips to the movies, or the purchase of a record player or radio. In 1939, the students at the Residential School near Hobbema, Alberta were taken to Edmonton to see the King and Queen during their visit to Canada—a gesture that many today will interpret as a horrifying rite of colonialism, but which the vast majority of Canadians then saw as a landmark historical event. After graduation, students of many Residential Schools would return to be married in the chapel, or even to come work at the schools as employees.

Parents frequently praised the Sisters for their achievements in educating their children—which helps explain why, on some reserves, parents actively opposed the federal government’s decision to close Residential Schools. The practical advantages of learning English were particularly well-understood. One Moccasin Telegrapharticle explained that

Lack of English among the Indians was often very harmful, because we have to do business with the white people who do not know our language. In that case, we have to depend upon an interpreter. This often works out badly. For example, he [Mr. Gullion, a local Indian agent] said, Indians often come to him after having made a horse deal, much dissatisfied with the bargain. When it is all explained, the Indian often has to say that this was not the way he understood it. If he could have understood English, he would not have made such a deal.

It is true, as has been abundantly reported in the media, that many Residential Schools suppressed the use of Indigenous languages, sometimes using indefensibly ruthless disciplinary methods in the process. But in many other cases, the opposite approach was taken. The Oblate Fathers, for example, made special efforts to learn Blackfoot and Cree, and often addressed students in those languages. Even Santa Claus is known to have spoken Blackfoot during at least one Residential-School Christmas program in 1967. At Onion Lake, the students were taught Cree syllabics so that they could write letters home to their families. In western Canada, many Residential-School students regularly won prizes for their art and performances at local exhibitions.

In a 2016 article published in the Canadian Journal of Economics, in fact, University of Victoria scholar Donna Feir concluded that attendance at Residential Schools actually reduced cultural assimilation, as compared to students at mixed public day schools: “Those children that lived with and went to school with predominantly non-Aboriginal people were, if anything, more economically and culturally assimilated than those who attended residential schools with their Aboriginal peers.”

One of the reasons why members of the Canadian public were so quick to believe 2021-era claims that hundreds of Residential School students in Kamloops, B.C. had been dispatched to unmarked graves was that they had already been told for years of the thousands of children from Residential Schools who’d simply gone “missing,” never to be seen again by their parents.

The ghoulish idea here is that a journey to Residential School was something like a trip to a gulag or concentration camp—a journey into a black hole of inhumanity, from whence nothing might emerge, not even information about the tragedies that unfolded therein. This is surely one of the most misleading aspects of the genocide narrative that has built up around Residential Schools.

Most schools were situated on or near reserves, so that students would be as close as possible to their parents, and to facilitate visiting on weekends and holidays. Students typically were admitted to a Residential School only after a parent had submitted a signed application, which was forwarded to Ottawa by the local Indian agent, together with a doctor’s certificate. There was an extensive bureaucracy surrounding the intake process. And the idea that school administrators were kidnappers who simply plucked students from reserves and then treated them as anonymous prisoners is wholly invented.

Once admitted, student attendance was documented in the quarterly returns that the school was obliged to submit to the government. It was very much in the school’s interest to hang onto every student in its care, since the grant for that student would be cut off at once if the student stopped attending, for whatever reason. Of the 150,000-plus students who passed through Residential Schools, at least 3,200 are known to have died at some point following their admission. And it is quite possible that the actual number is significantly higher. But the idea that whole legions of them could have simply disappeared due to mass-murder plots or similarly lurid narratives, leaving no trace, is profoundly ahistorical.

In addition, there was typically a constant stream of outside visitors to the schools—Indian Agents, police officers, doctors, dentists, nurses, X-ray technicians, dieticians, school inspectors, farm inspectors, and many officials from Ottawa. One reason why the government officials came was to pay the annual treaty money to which status Indians were entitled. The absence of any child on “Treaty day” would have been noticed and investigated.

A final bit of evidence worth noting: Former students often enrolled their own children in the schools, and returned frequently to the schools for visits. Are these parents to be smeared as agents of genocide?

Even the claim of culturalgenocide seems far-fetched. The First Nations Regional Survey covering 2015-17 reported that over 60% of adults who’d attended a Residential School said they could speak a First Nations language at an intermediate or fluent level. Furthermore, those who attended a Residential School were more likely to understand a First Nations language “relatively well” or “fluently,” as compared to those who did not attend (75% vs. 44%). This is not surprising given that several priests who’d taken a leading role in founding Residential Schools had shown their respect and admiration for First Nations cultures by not only creating alphabets and dictionaries for a number of their languages, but also by translating various texts.

It cannot be disputed that Indigenous peoples in Canada were mistreated in abundant ways. And it will be the work of generations to remedy that mistreatment. But it does these communities no benefit to warp the historical record by falsely employing the language of genocide—an idiom that separates Indigenous from non-Indigenous by portraying the former as timeless victim and the latter as timeless criminal. Canadian history, including the history of Residential Schools, shows many instances of these two communities interacting productively and in good faith, often developing great affection for one another in the process. In carving a path for the future, let us find a way to extrapolate from those inspiring examples, rather than engaging in apocalyptic exaggerations.

Thank you Bill, for all of your work, the value of which is under-appreciated.