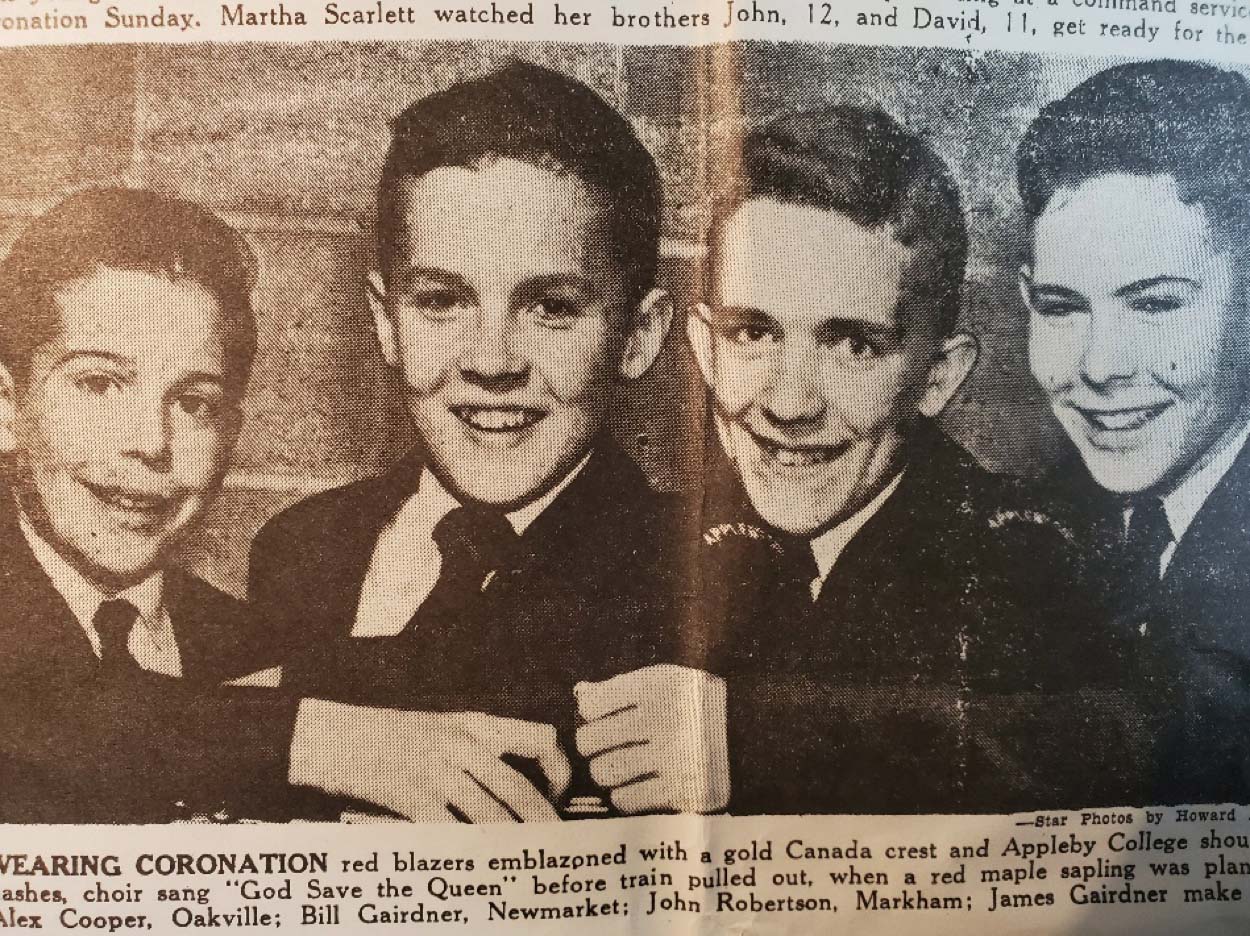

We never knew why, or thought we were good enough to deserve it, but in the fall of 1952, after winning the Kiwanis music festival prize for best boys’ choir, we were invited by the British Commonwealth Youth Movement to travel to England and Scotland the following spring on a six-week concert tour to help celebrate the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. That was the beginning of our misery. We were to miss all sorts of sports and endure endless tiring choir practices that year. But on May 7th of 1953, all decked out in our red Coronation blazers we embarked on the 21,833 ton Empress of Australia in Quebec City, and headed for Liverpool. Here is a photo of four of us – All Aboard! I am second from the left, and brother Jamie is on the right.

This was the maiden voyage of our re-christened ship. It was formerly the French luxury liner De Grasse which had been captured by the Nazis in WWII and used for naval cadet training and as a rest-ship for German U-boat crews. We sang for the passengers, and we sang for the crew. And halfway across the Atlantic we ran into a five-day, force-9 gale with 50 mile-an-hour winds. A lot of the boys were very sick. I remember seeing one of our boys puking over the rail in the wind. On its way down to the foaming sea the ejecta swirled onto the head of someone doing the same thing out of a porthole far below. A bad surprise.

Despite the rolling and pitching our choir practices continued at mid-ships. As she rolled, we saw only water from the large windows on the port side, and only sky from the large windows at starboard; then, the ship would lurch back the other way: sky/water, water/sky. We were delayed an extra two days at sea, and it looked like we were going to miss a special Coronation Service planned for St. Paul’s Cathedral in London for the day we arrived late in Liverpool. So the British government sent a special hi-speed train to pick us up, and on the radio we could hear what sounded like a national alarm as announcers whipped up the public about whether or not “the Canadians” would get to St. Paul’s on time for the service! Why, the train was rolling and jostling so fast you could hardly walk down the aisle, and all the while the nation was watching our race against time. Alas, we got to London on time, but got stalled in the worst stand-still traffic jam in English history, and so were late for St. Paul’s. Nevertheless, the English press was out in force, snapping shots of us running up the cathedral steps.

The Coronation itself was spectacular. In a day-long English rain we sat right outside the gates of Buckingham Palace on a high stand of wooden benches that ran the full half-mile length of The Mall, and the pageantry was astonishing. A moving fairy tale. Huge, beautiful, prancing black horses and white horses decked out in gold harness and white feather plumes passed us slowly by; knights in armour; the Queen’s guard in tall black bearskin hats, ever so stern in their metal chinstraps, swords pointing skyward; shiny gilt carriages of every sort; then, more beautiful horses – this time of our own RCMP – stamping and snorting, but under complete control. Then came the black Queen of Tonga, who seemed immense, and immensely cheerful, in her sumptuous purple dress. Riding in an open carriage, she was very wet, but smiling and waving, and drew the most cheers. Meanwhile, in the long pauses between carriages and horses, word got out that a Canadian choir was in the stands, and soon there was a clamour to have us sing for that soaking-wet crowd. So we treated them to some down-home Canadian songs like “Jack-the Sailor,” “The Huron Carol”, and then the beautiful “Goin’ Home,” by Dvorak, which really got them clapping. We felt like little ambassadors.

Three days later we sang in the majesty of Westminster Abbey at a special service for the new Queen, and then were off on our tour of England and Scotland for a month. We sang nineteen concerts, did two BBC Radio Concerts, and a half dozen lunch-time concerts, after which ham was always on the menu. It had just come off post-war rationing, and so everywhere we went our hosts delighted in announcing that there would be “ham for lunch,” at the sound of which, soon so sick of it, we nevertheless tried to smile graciously.

The impression made on us by singing, mostly unaccompanied, in places like St Martin-in-the Fields, in one-thousand-year-old Cathedrals like Winchester, Chichester, and York Minster, of hearing our own pure treble voices echoing their way back to us solemnly from lofty stone arches and columns, while peering at stained glass so bright in the sun our eyes hurt, was never again to be, except in lifelong memory.

As for the fun of it? We ran excitedly up the countless stairs inside the columns of a lot of cathedrals, and once high above, ran around excitedly among the bells and beams just like Quasimodo in The Hunchback of Notre Dame, peering down dizzily from the apex at diminutive worshippers milling about like ants below.

We also played cricket against a half-dozen English schools and lost horribly every time, but got to watch the English National Cricket team play at Lord’s famous London grounds. Then, on the way to Sedbergh School in Cumbria, in the hilly northwest of England we watched an entire field outside our bus window suddenly lift and move away at a great pace, only to realize that what we were seeing was a living carpet of a million wild rabbits running from our bus.

Once settled at Sedbergh, flash rains came, and we got invited to try traditional hill-sliding in the rain. We were handed very thick felt shorts and ran with a few dozen Sedbergh boys up a two-thousand foot hill in the Yorkshire Dales in a crashing storm. Floods of water fell from the sky and laid down the long grass, creating a whole weave of rushing sluices down which we were told to run, whence, at high speed, we would surely fall on our bums, and slide, down, down the whole mountain, in those felt shorts, water spraying high between our legs from the speed, careening between rock piles and grazing sheep to the bottom, where we arrived with very numb bums indeed. But what fun. We left that school to go to Edinburgh, and as the bus pulled away, we saw a man running after us in the pelting rain. But we didn’t stop for him.

Fifteen years later, the man running after the bus, who, to my immediate upset, called himself William Gairdner, showed up with his wife at our home in Thornhill, north of Toronto, to introduce himself to our family. I was upset to meet a man with my name. After all, it was my name. So, how could it be his, too? Turned out that he had been a teacher at Sedbergh, and happened to see our concert program with the Gairdner name on it, and went immediately into high alert, bolting after our bus to hail us down. A few years later he emigrated to Canada and took a job as a Professor of French Literature at the University of Winnipeg where, among other things, he translated and commented upon a fine book by the French Philosopher, Louis Lavelle.

Many years later I pieced it together that he was the son of William Henry Temple Gairdner (What? Another “William Gairdner”? By now, I surely had to give up the illusion that mine was a unique existence), who in his youth was a student atheist at Oxford University. But he had a roommate who fell very ill. So ill that no one knew how to help. So the atheist Gairdner looked after him, bringing him soup every day and changing his fevered clothes until he got so weak that at the end of the school term he died in Gairdner’s arms. So gracefully did he suffer and die that Temple Gairdner (as he was then known) became convinced there must be a God, else, how could anyone die so graciously? So he at once became a committed Christian. He was a very gifted fellow and a lovely writer, well-known in his day, but forsook a brilliant literary career in England to spend most of his life in the service of the British Church Missionary Society as the Canon of Cairo, where he died prematurely at 58 from a tooth infection at the height of his considerable powers. The Church of Jesus, Light of the World was immediately built in Old Cairo and dedicated to his memory.

I got his life story from a lovely biography I discovered in my Father’s library after he died, by Constance Padwick, his secretary, entitled Temple Gairdner of Cairo. It is a moving story, and in rendering the essence of a life devoted to the spiritual care of others, it gives the sense that he was as close as an ordinary human can come to living as Christ had wished us to live. He also had a lovely gift of language, gave sermons in Arabic within six months of arrival in Cairo, and published a number of books on literary and philosophical matters, including a best-seller called The Reproach of Islam. He was deeply persuaded that Islam, in which he was very interested, but with which he found serious fault, had only arisen in the world as a rebuke because Christians had not fulfilled their promise. This, along with the weekly journal he created called Orient and Occident (which remained a going-concern for more than half a century)was an effort to build mutual understanding between Christians and Muslims. Little could he have imagined – or did he? – that one day the World Trade Centre in New York would be attacked by radical Islamists, collapsing in an inferno of fire and twisted steel, and that terrorist organizations such as the Muslim Brotherhood would rise, as has happened so many times in history, to attack everything for which Christianity and Western civilization stands.

All that came from our Coronation Choir trip. Thirty years later we organized a reunion, and gathered together eighteen members of the original choir. We practiced a little with the new choirmaster, and then sang Ave Verum in the school Chapel. After a few wobbly minutes, the music and the Latin came flooding back. A little rough, but not too shabby, and we raised pledges for $20,000 to create a new stained-glass chapel window to commemorate our Coronation trip to England. Every beautiful English cathedral in which we sang is named in the red glass ribbons weaving through that window.